Welcome to the first of my interviews. For the first outing it’s none other than Video Game composer and awesome guitarist, Joshua Taipale. I had the wonderful opportunity to sit down with Joshua over Discord and discuss his musical influences and his approach to composition. What I loved about this interview was Joshua’s down to earth advice and constant drive to help others understand how music is appreciated and consumed. You will not be disappointed!

What’s your first musical memory?

Man… That’s hard to say. I’ve been around music all my life. My earliest musical memory is probably listening to NSYNC as a kid. I’ve always liked pop melodies. I don’t think I was really so aware of the music around me though until I played Sonic 2 for the SEGA Genesis when I was 7 years old. I vividly remember hearing “Chemical Plant Zone” and being stunned. I remember thinking “I never want to forget this” — I never did.

What was it about the track that made you so interested?

That staccato motif was so striking. It’s hard to say looking back on a time when I had no musical experience, but I think the speed and intricacy of the interweaving parts around such a simple idea left a strong impression on me. I still enjoy music like that. In my work as a composer, I try to create that experience for others — I want to stun them and leave an impression they won’t forget.

Sometimes that involves complexity, but sometimes simplicity can give that same level of taking ones breath away. How do you approach that? Any formulae you use or inspirations?

I think it’s a combination of things. Complexity can be impressive, but without something simple to latch onto, it might not be easy to remember. If you can create a simple yet strong hook to latch onto, then you’ll have more freedom to present it in a more complex fashion.

When I’m trying to hook the listener from the start, I try to write something very short — the shorter the better — with a unique line or texture to grab the listener’s attention. Billy Idol guitarist Steve Stevens calls this a “flag”, like the harmonic glissandi at the start of their song “White Wedding”. It’s the sort of thing you hear at a concert where the band plays just one note and the crowd immediately goes wild because they already know what song it is.

I guess that’s when you know you’ve really got a connection with your fan-base. Flipping the other way, how do you approach making music less front and center, how do you purposefully make it take a back seat, and do you ever feel conflicted?

There are several ways to do this. Reducing complexity (number, speed, and variance of moving parts) can help. Additionally, not every song needs a melody. That’s something I struggle with a lot — I always try to write one, and sometimes I forget that it’s okay for a song’s harmonies and textures to speak for themselves. That’s something I have to continually remind myself of.

This isn’t game music, but I challenged myself to do this when writing my prog-shoegaze band in Alto Mare (@inaltomusic)’s debut single “kairos” — I wanted to write a strong chorus that didn’t have a melody. I feel like I succeeded in that.

Mix engineering is something a lot of new composers don’t consider when dealing with this problem. There are many cases where you may need to mix a song a little differently for a game than you would if it were meant to be listened to alone. Final Fantasy XIV does a great job of this. The field and town themes that contain vocals have them swamped in reverb, lower in the mix than you’d ordinarily put them, allowing them to be present without distracting from dialogue or conversation.

My friend Garrett (@gwillymusic) did something really cool for a visual novel he was writing music for. He sent me a demo and asked for my feedback — initially, I said the kick drum needed a little more punch, but realizing it was for a hub area, I corrected myself and said that it was better as it was so it didn’t distract the player. He told me that he had the exact same thought process and that was why he made that mixing decision. It really impressed me and I think about it all the time.

It takes a lot of experience I think to be able to do that. Have you ever made a musical decision, something has been released and you’ve realised the decision was wrong? How do you handle that?

There’s a common saying that goes “art is never finished, only abandoned”; I think that holds true. Usually, I can tell whether the direction will be right or not as I’m planning a piece — I have a strong intuition. But sometimes, deadlines happen and I just can’t nail down the direction I want in time. In those situations, I remind myself of a piece of advice given by Arin Hanson on Game Grumps: “If it does what you want it to do, you’re done”. It’s another way of saying “perfect is the enemy of good”. In other words, it’s better for a piece to be finished and functional than to have a “perfect” idea that’s incomplete. It can’t be implemented in that state, after all. Above all else, I try to put my feelings into my music. If I can do that, I trust that they’ll reach people.

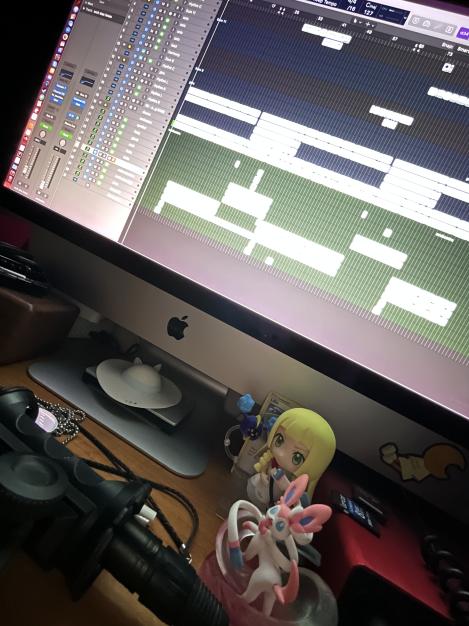

Joshua's Desk

Joshua's DeskPerhaps a difficult question to answer but, how do you personally put your feelings into a piece? With lyrics it definitely feels easier, but what about a commission? How do you inject emotion and cans you hear when people don’t?

When patch 5.3 of Final Fantasy XIV came out, it featured a vocal song that captured the attention of the fan-base. It was played during an important moment of the game and incorporated a number of its motifs, of course, but there was something about it that players just knew was special. It was later discovered that the composer (Masayoshi Soken) wrote it while battling cancer — he had put his feelings of determination into the music, and the players felt that.

I think music, and all art, speaks to the soul in a way that’s deeper than ordinary words. There’s something divine about it. I just have faith that if I let my feelings guide my writing, those feelings will reach people — not everyone, but enough. That’s not to say I don’t temper those impulses with a logical understanding of the functional goals of the music, but when I’m stuck, I let those feelings drive me.

I think that is honestly what every listener wants to hear. Music that connects them. Are there any pieces that you connect with deeply?

Far, far too many to list! In regards to moments from video games, though: Any time I hear a piece of music in a scene and have to stop playing to listen to it before continuing. “Corridors of Time” from Chrono Trigger was like that for me. I still remember loading into Antiquity for the first time and being stunned by the music and the setting. I went into that game blind so I’d actually never seen or heard that chapter before. The music took my breath away — it’s like beaded curtains swaying in the wind, framing the door to a place both ancient and eternal at the same time. I sat there taking it in for about five minutes before I kept playing.

Do you think as musician/composers we are more deeply affected by music in this way?

So, there have actually been studies done on this — people who score high in a personality trait called “openness to experience” tend to be creative people. They also tend to feel their emotions more deeply than others. So I think that’s true to a certain degree. But whether musicians specifically are more deeply affected than the average emotional person, that’s hard to say. In one sense, we “understand” more due to our familiarity with music as a language, but then, our experience is different from that of someone who’s ignorant to those things. I might say we experience music “differently”.

Music as a language had always been an interesting concept to me. To what degree do you consider this when composing for a client? Is it a universal language? And if not how do you go about working on the ‘dialect’?

People argue about this every few weeks on Twitter, but the answer depends on what you mean by the question. Our understanding of music is shaped by both our physiology and psychology, our culture, and our own upbringing. As a result, no two people will experience a piece of music in quite the same way — but their experiences will likely be fundamentally similar.

We translate and localize lyrics because words are defined — you might be able to appreciate the beauty of a word’s enunciation and structure, but you won’t glean much else without knowing what it means. Music, on the other hand, might be the most abstract of the arts. It’s primeval — there’s research that suggests we sang before we spoke. We might not all interpret the nuances of a piece of music in the same way, but no one has to tell you how you’re meant to feel when you hear “Kakariko Village”.

Cultural differences tend to come up more in regards to trends — especially when writing music that’s meant to sell. What one audience might consider old hat, another might find more engaging. There’s also something to be said for cultural awareness in writing certain genres authentically, but that’s a different subject, I think.

That’s not to say there’s nothing worth considering when writing for a particular audience. I think when writing game music, that’s far more important. If you’re making a visual novel, for example, people tend to expect a certain type of music. In being aware of those expectations, you can meet or subvert them accordingly depending on the experience you want your players to have.

Above all, I just trust that if I put my heart into my music, it will reach people regardless of where they come from. It hasn’t failed me yet.

Joshua Taipale

Joshua Taipale